Why you should get better at disagreeing

How to understand things better by listening, understanding and explaining better

Disagreeing is easy. Anyone can disagree. But disagreeing well is difficult, and far too rare. The skill of dissenting is central for making better decisions, especially in complex issues. In healthcare, it can literally be a matter of life and death, and outside of healthcare it can be life-changing. But we spend little time developing this skill. Let me explain.

Making decisions involving many unknown variables is challenging. Most often, you won’t face the trickiest decisions alone, but with your partner, family, or colleagues. We choose to make those decisions with input from others not despite, but because they have different views - it’s a feature, not a bug. Combining perspectives helps us understand things better and make better decisions.1

However, combining truly differing perspectives means disagreeing. There are many names for this (productive tension, purposeful discomfort, constructive conflict etc.), but despite all the labels, we tend not to practice on the skill of disagreeing. Throughout my career, I've learnt to disagree about many different things. Disagreeing in many different contexts (e.g. ranging from disagreeing on patient management in clinical settings and when building companies, to disagreeing when serving on boards and management teams) has taught me that some principles are useful regardless of the setting.

This text is a collection of those principles and mental models, which have helped me and will hopefully help you too - regardless of whether you work clinically or in the boardroom.

1. What: Disagree on things that matter

There are many things to disagree about, and we sometimes waste time on things that don’t matter.2 Develop a habit to reflect before challenging something, and only disagree on central points.3

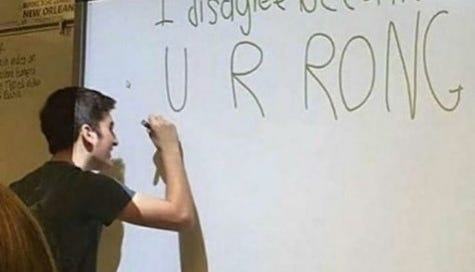

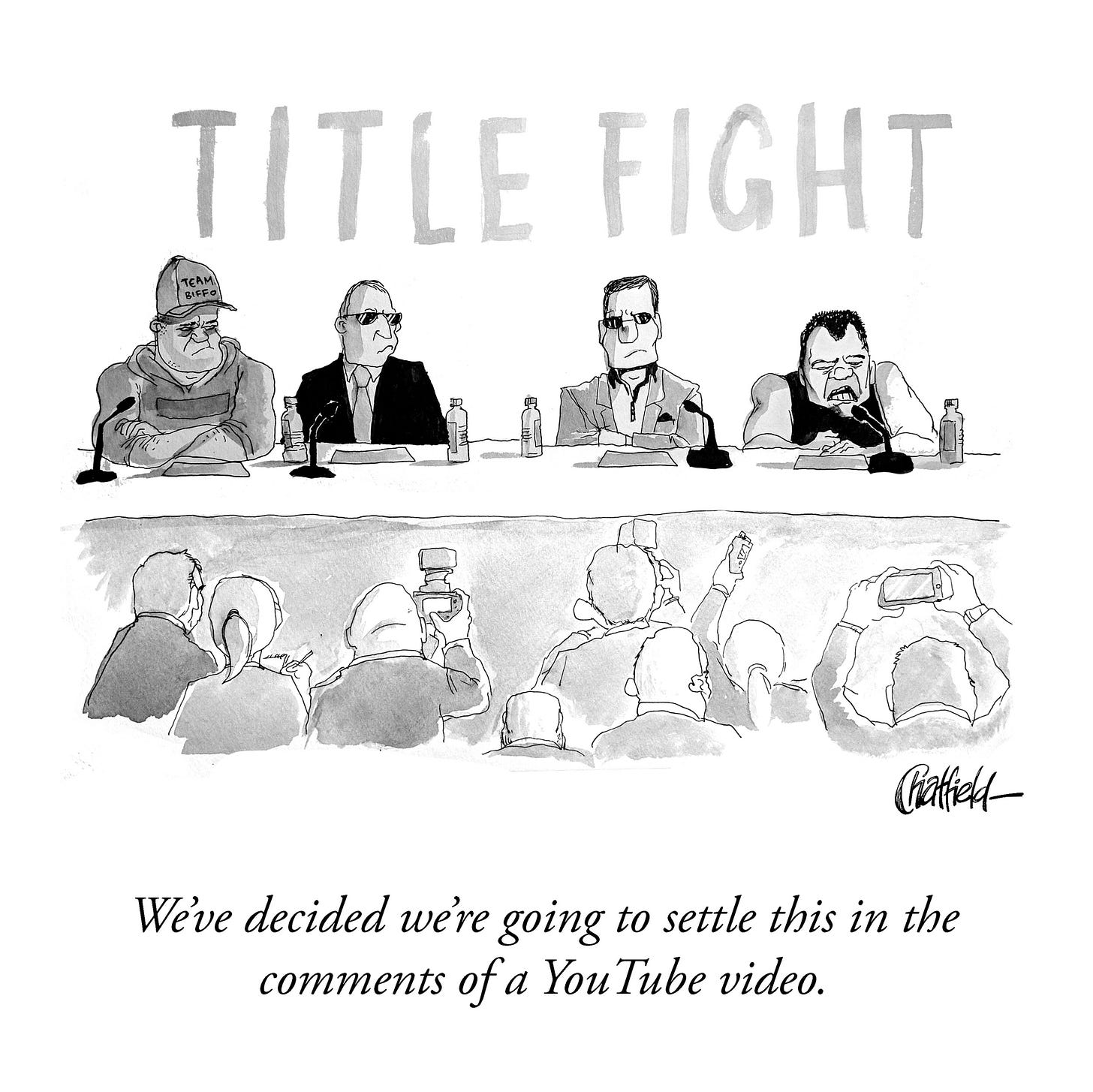

Life is too short to debate trivial matters. Don’t engage with irrelevant arguments or pseudo-arguments. Instead, internalize Paul Graham’s hierarchy of disagreement and stay on the top two levels. The question then becomes “How do I learn to disagree well?".

First, disagreement isn't conflict. Disagreement describes two parties having different opinions - after a discussion those opinions might converge or not, but no one has strong feelings about it. Conflict consists of a disagreement and parties assuming that the disagreement is due to a fault in the other party.4

In many cultures, disagreeing with superiors may be seen as rude. I sometimes experienced that when I questioned a senior physician’s opinion on how to manage a patient. At the same time, the high stakes in medicine forces one to realize that disagreeing with someone’s opinion doesn’t mean having a conflict with that person.

Secondly, disagreeing is a skill that can be improved. Like any behavior: if you reflect and practice, you will improve. I believe there are three important principles to disagreeing well which are worth practicing: listening intently, understanding the opposing view, and expressing your thoughts concisely.

To make this concrete, imagine this exchange in a hospital’s board:

Head of Oncology: "… that’s why we must adopt this [new screening technology] as soon as possible. In summary, it detects cancer much earlier than our current methods and will save many lives. To be honest, delaying its adoption is simply negligent."

Hospital CEO: "Look, I appreciate the innovation, but we’ve seen this before. The last time we rushed out new technology, two years ago, it caused chaos because the practical impact wasn’t thought through properly. In this case there are many false positives that will cause a lot of extra follow-up and cost a lot. Those costs aren’t clearly described in the articles you showed. Our teams are already stretched thin now before the holidays. I have to say, this feels a bit like that time."

Independent Board Member: "We know that our staff is already stretched thin. Can we really add more things for them to do? Sorry to be direct, but this is a bad idea. We need to focus."

Head of Oncology: "Bad idea? So you’re saying we should just ignore a chance to save literally thousands of lives by introducing one little change in our process? That’s what it sounds like. We’re in the business of improving patient outcomes, not micromanaging spreadsheets."

Hospital CEO: "That’s unfair, and you know it. Nobody here is against saving lives. But we can’t ignore what this means for our staff. Right now, we’re all overburdened, and this just adds another layer of strain. It’s great publicity for the hospital, and especially the oncology unit, but you’re asking other departments to pay a hefty price."

Head of Oncology: “What do you mean with great publicity for the-”

Independent Board Member: "Alright, listen, clearly this is a complex issue. Maybe we need more time to think this through. Let’s table it and think it through, and revisit it at the next meeting."

All three parties may be correct, but the way they listened and talked to each other made it difficult to reach a good decision. The next section will highlight the practical tips which could help them, and us, disagree better.

2. How:

2.1 Listen intently

Do your utmost to really understand the opposing view. This is the easiest way to listen intently.5 Remember, understanding someone’s argument doesn’t necessarily mean agreeing. Temporarily trying to convince yourself of another perspective will often help you draw the same assumptions as that person and understand their chain of reasoning (and some of the times you’ll realize that they’re correct and that you’re wrong). These techniques help:

Be curious. Be intellectually honest and be ready to change your mind.

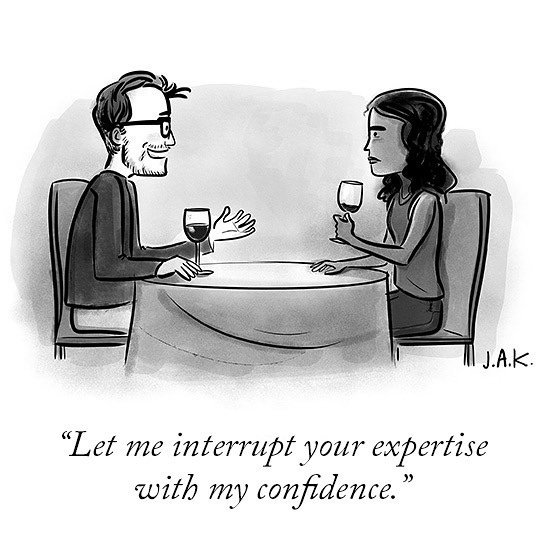

Act curious.6 State out loud that you are curious. For example, use qualifiers like “I get that some people might disagree, and I would like to learn about your perspective” to actively commit to being curious and actually giving others’ perspectives an honest chance.

Assume good intentions. Don’t assume that someone with an opposing view is wrong, mean or evil - assume the opposite.

Avoid isolated demands of rigor. Sometimes, it’s tempting to dismiss an argument opposing your view. Before you do that, try the Ctrl+H test. Ask yourself, if the same argument with opposite content supported my argument, would I still reject it as strongly? In other words, is it the argument itself, or the conclusion which doesn’t support my view, which I struggle to believe in?

In the example above, the Hospital CEO could have asked herself "Before I dismiss the screening technology due to concerns about false positives, let me ask myself: if the study instead showed the same rate of false positives for a technology that reduced costs but didn’t improve outcomes, would I still be this critical? Maybe I’m holding this technology to a higher standard because it’s challenging my budget.”

Ask steel-manning questions. Ask clarifying questions in order to strengthen the opposing view - questions designed to help the other person provide more supporting data or information.

In the example above, the Board Member didn’t add to the discussion by referring to a historical example (even if it’s true, it’s not relevant for the central point that the Head of Oncology raised). Instead, she could have steel-manned the Head of Oncology’s perspective: "I understand that you see this technology as a game-changer for early cancer detection. There are false positives which aren’t described that well in the articles, but what assumptions would we have to make to conclude that the benefits outweigh those problems?"

Dissolve the argument. Ensure that you are using the same definitions. Break the topic into smaller parts to understand where you agree and disagree.7

In the example above, the team could have put names to the different aspects of the suggestion and made it clearer what they had to figure out. For instance, they could have clarified that they had the same goal but have to understand (a) the benefit in their setting (b) the costs, including false positives and increased work load

Practice this. Practice this. And practice this.

2.2 Understand well - Rapoport’s rules

Beyond listening and taking in information, it’s valuable to check that you’ve understood the other person. A good way of doing that is repeating their argument back to them, and the best way is by following the so-called Rapoport’s rules8:

Re-express the other's position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that they say, "Thanks, I wish I had thought of putting it that way."

List any points of agreement (especially if not everyone else agrees)9

Mention anything you've learned

Only thereafter, express your opposing view

As part of (4), it’s useful to label points of disagreement in neutral terms (e.g. “we seem to disagree due to you valuing X slightly more than Y, whereas I value Y slightly higher”).

If you do this, you’ll see that very different opinions often only differ when it comes to small fundamental and basic differences - e.g. slightly different assumptions, values or weights on different factors. And reaching that conclusion, by itself, can be useful.

In the example above the Board Member could have summarized the Head of Oncology’s perspective before questioning the impact.

Board Member: "Let me try to summarize your position: You’re advocating for adopting this screening technology because it detects cancer earlier, which could save lives, and you believe these studies show that the benefits would outweigh the risks of false positives and costs in our setting. Is that accurate?"

Head of Oncology: "Yes, exactly!"

Board Member: "I also think saving lives is critical. But I’m unsure about the impact of false positives and the downstream costs in our context. I’d feel much more confident if we could pilot it here first to gather more data."

2.3 Express clearly & be kind

This section expands on point four of Rapoport’s rules. The goal is simple: Make it easy for others to understand you. To disagree well entails understanding others, as well as making it easy for others to understand you. To do that, you want to express yourself concisely, in a structured and easily understood manner.

Be easy to understand

Be concise: Use as few words as possible to state your argument.10 This will force you to think through your arguments and not waste time. It also shields you from being vague or imprecise. What is vaguely said is vaguely thought,11 and contributes poorly to discussions. Aim for the opposite of a Gish gallop.

Be structured:

Signpost when stating longer or several arguments: Say what you’re going to say, say it, and then summarize what you said.

If stating several arguments, follow the rule of three: Use three arguments, no more, no less. Three arguments is easier for a counterpart to keep in mind, maybe because our working memory seems to be able to recall 3-4 things at the same time12.

Easily understood: Use simple and exact words. Avoid metaphors and similes unless they add clarity.

Be kind

Be polite and nuanced. Consider sometimes using softer phrases like "I'm not sure I agree with that", instead of outright saying "I disagree". That doesn’t mean you can’t be clear, but being polite seems to be more effective in helping others understand your perspective.13 This is culturally dependent, but remember - it’s better to be clear and understood, than polite and misunderstood.

Give your counterpart opportunities to save face. If pointing out factual errors or misunderstandings, don’t embarrass them but rather explain how that mistake is easily made. Be kind. Discussions are about learning, not winning. 14

Understand, don’t win. Internalize that, and you’ll never have a reason to be unkind.

In the example above, the Hospital CEO could have been more supportive and given the Head of Oncology an opportunity to save face, for instance

Hospital CEO: "I’m really grateful you brought this up. Without you scouting for new innovations we‘d be much slower in improving our care. I also see potentially huge benefits, but my main concern is the operational impact due to false positives. If we knew that was manageable I would fully support this. How can we figure that out? Could we talk to other hospitals that have implemented it and hear about their experience? Or could we explore it through a pilot program? That could maybe allow us to test the technology in a controlled setting, measure its impact on outcomes, and address any concerns before a full roll-out. Or what do you think?

3. Why: Life is short

Why spend time on learning to disagree, rather than many other important skills? I think it helps you understand things better, foster trust and decrease frustrations. Disagreeing well…

Helps you understand things. In most situations, there is much more to gain by understanding the world and what’s true, than by trying to prove your point and ignoring opposing information. It’s easy to fall into the trap of common cognitive biases (confirmation, false consensus and overconfidence bias), and end up making wrong decisions. By learning to disagree well, you will understand the world better by absorbing as much knowledge from others, and also by stress-testing your own ideas and arguments.

Fosters trust. By admitting when you’re wrong and showing that you actually want to understand the world, rather than solely be right, you give others reasons to assume good intent. As with any well-willed behavior, this fosters reciprocal behavior in the long run.15

Decreases frustration. Never disagreeing means you have a limited impact in your context. Disagreeing poorly can be counterproductive and frustrating for you and others. But disagreeing well optimizes for both interaction and understanding, and will make for more enjoyable days.

4. Emmetropes

Practice disagreeing: it’s an underrated and transferable skill

Practice being curious: optimize for understanding rather than being right

Avoid isolated demands of rigor: Use the Ctrl+H test

Follow Rapoport’s rules of constructive criticism

Be easy to understand and be kind - express your ideas concisely, structured and in easily understood ways, and be kind to your counterpart

Thanks to Amanda Chen and Charles Margarit for reading drafts of this and offering useful feedback.

For example Price et al 2010

For example, how many days there are in a week, whether a hotdog is a sandwich (solution here) or what color a dress is.

My corollary to “do you want to be right or do you want to be happy”

Cfr Hemingway's "When people talk listen completely. Don't be thinking what you're going to say. Most people never listen.”

Again, Julia Minson

Named after the mathematical psychologist Anatol Rapoport who devised a code of conduct for offering critical commentary that would advance discussions, which was then summarized by the philosopher Daniel Dennett. Read more here

E.g. Maia et al 2020

Since several decades I try to follow the Swedish adage “Skriv kort, helst inte”, i.e. write briefly, preferably not at all. Expression originally coined by Sigge Ågren, a Swedish journalist.

Again a Swedish saying: “det dunkelt sagda är det dunkelt tänkta”. Originally from a meandering poem by Esaias Tegner written in 1820

Also Ming Chiu