Memento Yamato

Why should you get cancer now? Why don't smartphones weigh 68,000 tonnes? What is Emmetropia?

Progress is incredible, inspiring, and most of all: important. A example that is relevant for you (yes, you who are reading this):

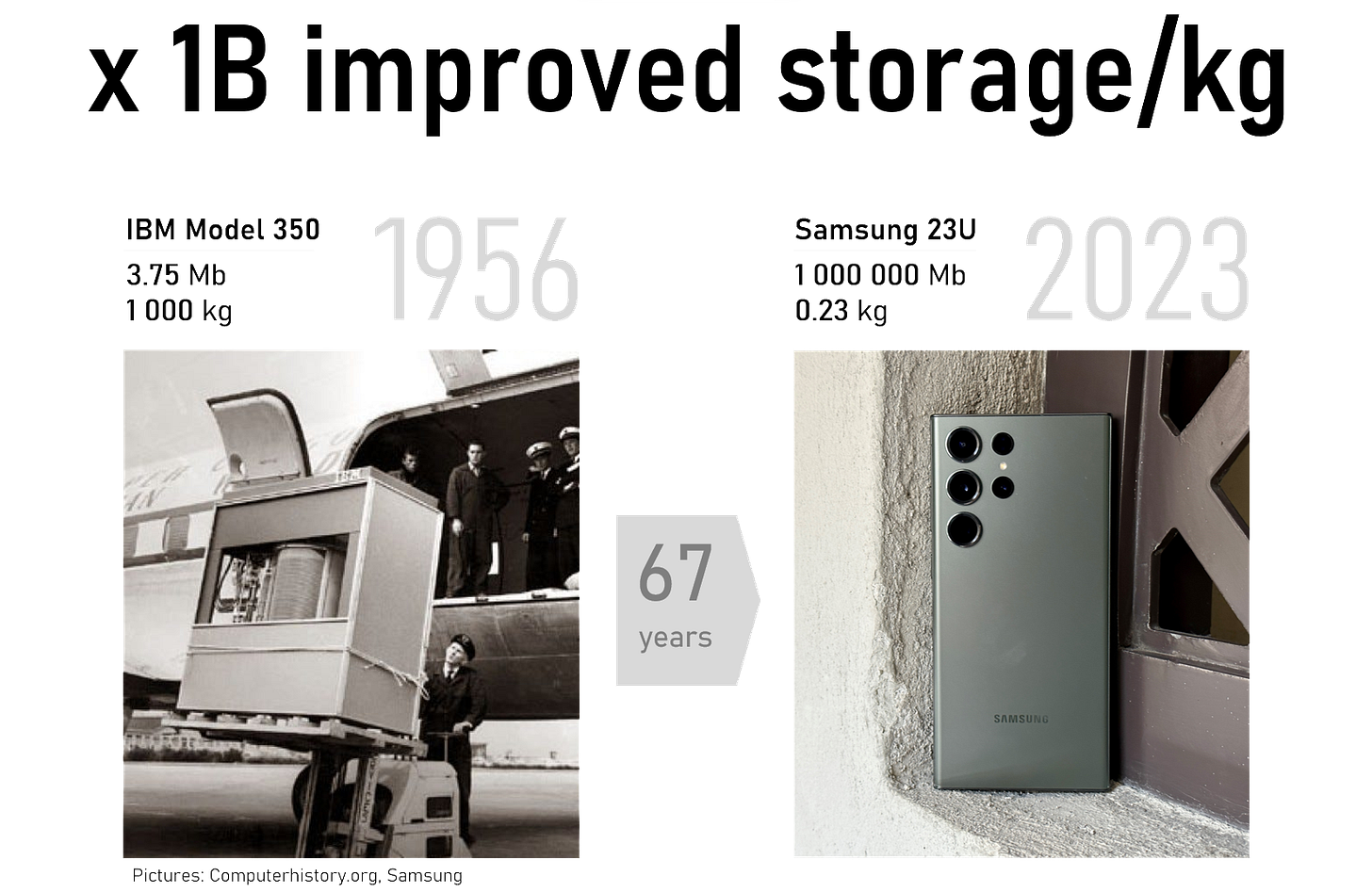

- In 1956 a new hard drive weighed 1 tonne and stored 3.25 megabytes.

- In 2023 a new smartphone weighs 230 grams and stores 1 terabyte1.

Think about that. In 67 years, the storage per weight has increased over 1 billion times.2 No matter how hard you try - no one can’t grasp a number that big. Our brains struggle to understand that large numbers.3 1 billion is a lot. A billion seconds is 30 years. Even this picture doesn’t really capture it.

This type of progress is crucial for humanity. Researchers, scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs have decade after decade, in many different languages, asked the question "How can we improve this?". And thanks to them a poor street kid with a smartphone today has better access to information than kings and queens have had throughout most of human history.

And this is why you can read this text on the little screen in your hand. Without any progress, just your phone's memory would weigh ~ 68 000 tonnes, nearly as much as the Yamato, the heaviest battleship ever built.

Source: Nationalinterest.org. This illustration and other photos of the ship convey that the battleship was built according to the principle “have the mostest of everything”, which didn't turn out to be very effective.

Improved storage enabled other types of progress, in a near exponential manner. All the things you do with your smartphone - none of that had been possible if we hadn’t improved storage technology.

But this isn’t about phones and battleships

Sorry, I tricked you. This isn’t actually about smartphones and battleships. But why do I feel so strongly that we need to understand progress?

Because we forget about it. We forget that certain types of progress - progress that truly raises the bar for something that aids humanity - has a value far greater than the medial publicity, or a company’s market cap or competitive advantage. Progress that really raises the bar - from which humanity will or can not return - has an impact that stretches forward for all of humanity for all foreseeable future, unlocking the next wave of improvements for generations to come. Understanding the huge size of the impact is just as difficult, if not more difficult, than understanding how big 1 billion of something is.

This time aspect of progress is particularly salient in medicine. Thanks to humanity’s combined but imperfect effort, we do things today that were unimaginable 50 years ago, unthinkable 25 years ago and impossible 10 years ago. We should feel as strongly about medical progress as we do about the lives of our loved ones - as these two are deeply interwoven.

Progress in medicine is illustrated beautifully by the drug Imatinib (Gleevec). Imatinib was approved by the FDA for treating a blood cancer called chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in 20014. Before Gleevec only 1 in 3 patients survived CML5. With Gleevec they have nearly the same life expectancy as the normal population.6 Few things have such a tremendous impact.

This (slightly confusing) graph shows how CML patients’ survival has increased for each decade.7

This graph should win first prize in the category: “Portraying medical progress in an elegant way with as confusing a legend as possible”.

Several clinicians have criticized Imatinib’s initial high price8, and the price aspect merits a separate and deeper discussion. But taking a long term view, the value of Imatinib is not just all the patients that are helped by it today - but all other research and innovations it's accelerated and enabled.9 It raised the bar for the future of all humanity.

Imatinib isn't unique. Similar improvements have occurred for other cancers. That is why there has never been a better time to get cancer than now. Let that sink in. There has never, in the history of mankind, been a better time to get cancer than now.

Read that sentence again and imagine how different the world would be if your loved ones had the same mortality rate as we had in the early 1900s.

The philosopher Epictetus is said to have told his disciples to remember that they were mortal whenever they embraced a friend or relative. Memento mori. Tempus fugit. And I write the next phrase hoping that most readers have given up by now and that you won't see how much shame I feel: YOLO. Useful mantras (well, two of them) to remind us how brief life is and that we should do the most of it.

But they all miss progress. They disconnect the brevity of our lives from the larger context, and that our short moment has become so much sweeter thanks of those that came before us. And also, any phrase starts losing its original pathos after being tattooed inaccurately across thousands of forearms.

Can you spot all four errors in the picture? Answer and source in the footnote10

So I propose something else.

Don't say Memento Mori when you embrace a friend or relative.

Say “Memento Yamato”.

Think of the Yamato and your smartphone, think of Imatinib and remember how important progress is, even if it’s greater than our minds can grasp.

But wait, is anyone actually against progress?

A reasonable response to the text above could be: “Ok, cool. So maybe we forget exactly how much progress we make. But no-one is arguing against progress, or actively trying to stop progress, right? I’ve never seen politicians campaign on less progress or bigger hard drives. So is this really an issue?

I'm happy you asked, dear hypothetical reader, because that's the problem. It's not anti-progressites, but that we generally prioritise other things higher than progress.

Let me give you three short examples:

Institutional research boards (IRBs) optimize for safety, not progress

IRBs, or ethics boards, are essential for modern science. An IRB is a committee that assesses planned research proposals to ensure that they are ethical. If they find potential risks they can reject the planned research or demand amendments. Their main goal is to ensure that no patient ever is harmed in any way. Considering many historical examples where patients have been harmed, this sounds good, right? However, they have no incentive to ensure medical progress. This means that IRB processes often can results in unnecessary delays, costs, or that studies aren’t performed. Delaying studies can cause delayed treatments - which means that people continue dying until the study is done.11

Do you want to send an anonymous multiple choice survey to medical students about fictional patient cases? Be prepared to spend over $120 000 and 50 person-months during 16 months getting relevant IRB approvals.12

Don’t get me wrong. IRBs are needed, but have to be reformed urgently. We shouldn’t unnecessarily hinder researchers from performing safe studies that humanity needs.

Most of scientific knowledge is paywalled

Do you find paywalls on homepages frustrating? Well, 72% of all research articles are paywalled, and individual universities paid up to $1M per year in 2009 just to access a fraction of that knowledge. Some of you might be unfamiliar with how scientific knowledge is published and communicated. In brief

Governments (or other funders) give money to researchers so they can perform and publish research

Researchers perform research and publish results in journals

Scientific journals charge universities and people to read the articles that the researchers have published in their journals (paywall).

Turns out that if humanity needs knowledge, and you’re a publisher with a paywall restricting ~16% of all research, you can charge a lot of money for it. This is slowly changing towards an open-access system, where certain journals make research articles freely available. However, every year there are researchers who make slightly worse decisions due to not having access to all of the published literature. Or universities who spend money on paying for paywalls instead of supporting actual progress through research.

We remain superstitious and ignore science

More than 40% of Americans believe in ghosts, demons or supernatural beings. Around 75% of Americans believe in telepathy, reincarnation, witches or other paranormal phenomenon. There might be a religious confounder, but even in secular countries like Sweden, more than a third of the population believe in paranormal phenomenon and ~20% believe in telepathy.

This is the most interesting question: Why do so many fewer people believe in vampires compared to demons? Religion? Was Twilight so unrealistic that it left a dent in the US population’s belief in Vampires? Vampires being disproportionately slayed in Buffy?

These three examples show that we are struggling to create, spread and adopt knowledge. There’s no mystical anti-progessite. We, as a society, are failing ourselves.

The question that needs answering

I hope you by now agree that progress is important with a capital I. But it’s often undervalued or neglected, especially if you take a shorter perspective of a year, business cycle or election period. So if progress is important - how can we overcome these constraints that nudge us towards less optimal choices?

The answer is as simple to write as it is challenging to achieve.

A well-informed electorate. A society that teaches children to be curious, be inquisitive and think critically. Companies, organizations and investors that take a really long perspective. Citizens that avoid tribalism and simple truths. Decision-makers that take a long view and that can see the horizon clearly with relaxed eyes, without any refractive errors.

I hope this answer resonates with you. If it does, I’m sure you’ll enjoy the coming texts.

Welcome to Emmetropia.

Sources: Computer History Museum (lots of interesting tidbits!), Samsung (not as many interesting tidbits)

1 139 601 140x to be precise, but who’s counting? Well, most likely you, me and the other people who read footnotes. To be honest, I’m really happy I’ve attracted a reader like you! Ever since I read Terry Pratchett I’ve been a devout footnote reader as well. Fun fact: his biography’s title is Terry Pratchett: A Life With Footnotes.

If you find this interesting, and I hope you do, there’s some really good reading in Landy 2013, including how this can affect peoples’ perceptions of potential policies.

You can read more about Imatinib in the introduction section in this paper

Varies across different countries, but basing on historical cancer.net statistics

So much that there’s even a section in Wikipedia about that.

1. Believing that Greek letter are interchangeable with Latin script

2. Mistaking the ℞ symbol for a Greek letter

3. Using Greek letters for a phrase in Latin

4. Getting the tattoo.

Source: Hellenic History

For a entertaining description of the absurdities of the IRB process, read this. For a more comprehensive text, with some examples, read the book from Oversight to Overkill, or this review of the book. Read this article for some brief examples

Unfortunately this is not a made up example. If you are a researcher you can’t really do anything about this, except publishing passive-aggressive articles about your experience.

Är inte kulturella men också demografiska faktorer avgörande för innovationsgraden? Anta att vi har en bra reciprocal altruism-sekulär-upplysningsideal-kultur på plats. Då behöver vi ändå (tycker tex. peter zeihan)många unga personer som kan vara innovativa; samt mkt billigt kapital som kan investeras - vilket också beror på befolkningens åldersstruktur då vissa livsskeden (…som man äter livsglassen med!?) innebär större sparande.

Tänk om ”för/mot progress” avgörs på kulturell evolutionsnivå, och när vi väl lämnat släktskapsintensiva klansamhällen bakom oss är det strukturella faktorer som avgör? Så kanske ”long perspectives” för ”companies” är skitsamma. Kortsiktig rovkapitalism räcker så länge demografin är ung och kapitalet billigt - och när så ej är fallet kanske inte nyfikna barn och välutbildad väljarkår varken gör till eller från.

?