Why does healthcare have so much administration?

Why healthcare administration is so problematic, why it's growing rapidly, why it's unavoidable, why it can be good, and most importantly: what can be done

I. Healthcare admin is increasing & it's pretty bad

You’ve probably heard people complain that there’s too much administration in healthcare. Is it really that bad?

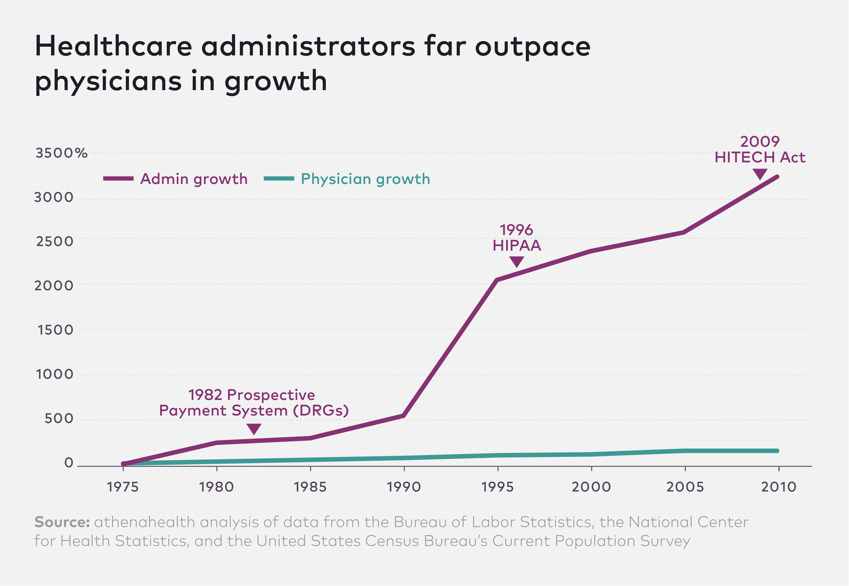

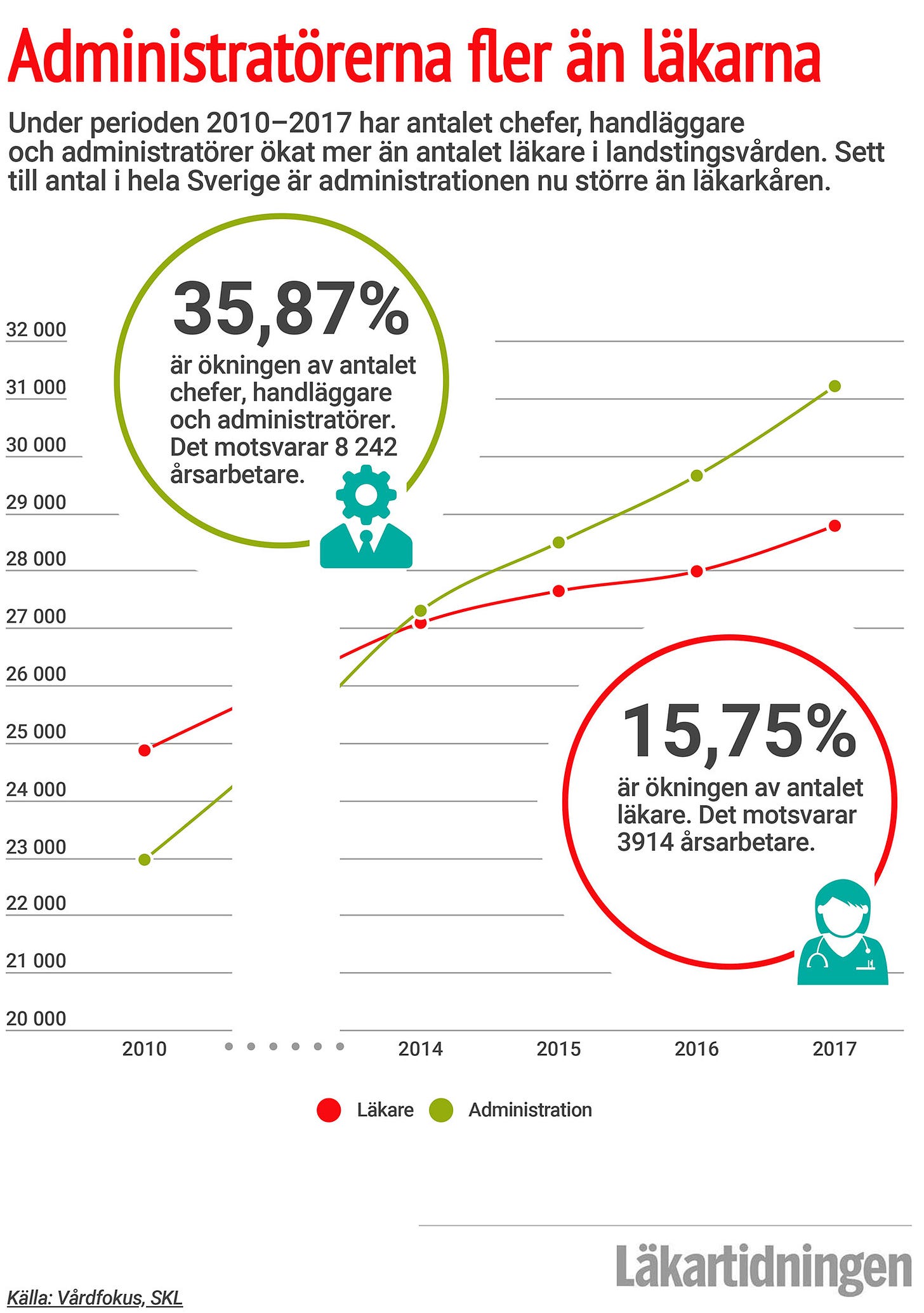

Let me answer with this graph showing the growth of US healthcare administrators and physicians:

Graph nerd comment: Any graph with a y-axis that surpasses 1000% is poorly calibrated, misleading or both.1 More about that later.

Healthcare administration is about 15-25% of the US healthcare expenditure. While the number of US doctors grew by 150% between 1975 and 2010, administrators have increased significantly, according to the graph above at a rate of 3200% (relative increase of ~20x).

This isn’t just in the US. In Sweden (that has a publicly financed healthcare system) it’s the same. Between 2010 - 2017 the number of doctors increased by 16%, while administrators increased by 36% (~2x relative increase) and since 2014 outnumber doctors.

Is this a problem? Well, yes, if you read articles like Excess Administrative Costs Burden the U.S. Health Care System, The Astonishingly High Administrative Costs of U.S. Health Care, The Great Healthcare Bloat: 10 Administrators for Every 1 U.S. Doctor and Healthcare bureaucracy growing despite lack of healthcare staff.

Or just ask anybody who has ever worked in healthcare.

Increased administration is seen as problematic as it takes money (which instead could be spent on clinical staff) and time for clinical staff (which instead could be spent on providing care).

And a lot of clinicians’ time is spent on administrative tasks. In Swedish time studies, 40% of clinicians’ time was spent on administrative tasks. Another study found that only 25-40% of clinical staff’s time is spent on direct patient care, and that a majority of the rest of time is spent on administration. Take electronic health records (EHRs) for example.

EHR usage takes time: Around 30% of clinicians’ time is spent on documenting in the EHR.2

Documentation is often duplicated in EHRs. EHRs have large bodies of text that are difficult to navigate and take even more time for clinicians to navigate. This varies across countries and contexts, but up to 40-50% of EHR text content seems to be duplicated information.3

It wasn’t always like this. In 1943, an in-hospital stay of 2 months could result in a medical note that fitted on an A4 page.

A hospital stay of similar length would today result in something significantly (> 10x?) longer. This increasing documentation is bad for several reasons

takes more time for the clinician to document the note

takes more time for every subsequent clinician to read the extra information

patient safety risk where its difficult to find relevant and pertinent information in the notes due to lots of other information that is irrelevant for the task at hand

When I worked at an orthopedic ward it was common for nurses and healthcare assistants to write several notes a day, and a doctor would write a note every day. Some other examples of administrative tasks I experienced while working clinically:

Lots of clicks just to start writing in the EHR: Accessing a patient's medical record: Insert my identification card into a card reader. Enter a code. Press enter. Wait for the computer to unlock. Unlock the EHR with another code. Click the search patient button. Enter the patient's social security number. Press enter. Click the medical note button, find the right template, click on that. Click on the sub-header. Click in the writing field.

Writing discharge notes for patients I’d never met: When a patient leaves the hospital the doctor writes a discharge note, summarizing what happened during their stay. However, sometimes doctors forget that. And if that doctor had stopped working or was on vacation when it was discovered, a junior doctor would be tasked with writing the discharge notes. For complex patients that means sifting through a trove of historical notes and writing a summary for a patient that already left the hospital and was receiving care somewhere else. Also, what is the purpose of writing the note if I don’t know the patient well, and risk writing a summary that misses important medical details?

Transferring information to quality registries: When I worked as a junior physician at the emergency department I met patients with heart attacks. After admitting them I would get the task of filling in a paper form by hand. This form would later be collected by a secretary and manually fed into the digital heart attack quality registry. The irony was that the data that was added by hand was information that was already existed in the EHR. But as the EHR didn’t communicate with the registry system, it had to be manually written on paper.

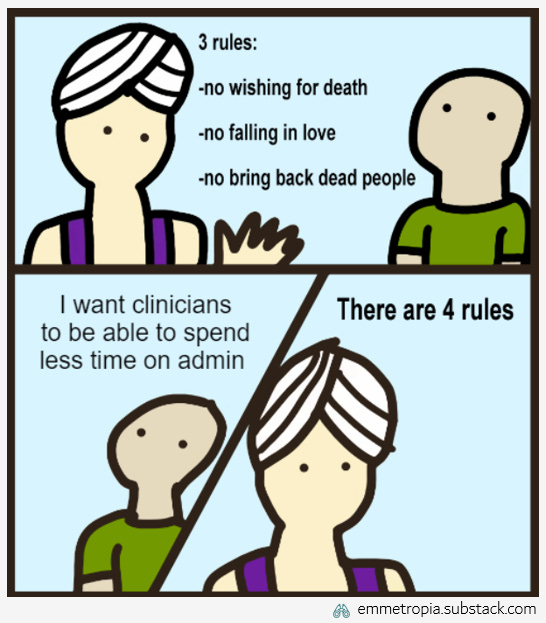

I have never met a clinician who doesn’t feel that healthcare admin has to be reduced. But the thing is: admin has and will continue to increase.

I believe that medical progress is deeply important and needs to continue. But medical progress creates more administration, not less.

II. Administration increases as healthcare improves

Let’s be specific. Firstly, by administration I refer to producing or consuming written information about a patient (group) without the direct involvement of the patient.

Examples of producing: Documenting in the EHR, quality registries, economic reimbursement systems, incident reporting systems, as well as writing referral and referral responses, letters, sick notes or other documentation.

Examples of consuming: Reading medical records, aggregate quality metrics, referral and referral responses, or test results.

Secondly, what does it mean for healthcare to improve? That’s a tricky question4, but I’d argue that healthcare has improved if you see improvements in:

A. Knowledge and capabilities: healthcare providers know more and can do more than before.

B. Outcomes: patients’ medical outcomes are better than before.

C. Lifespan: patients live longer than before.

D. Transparency: society has a better understanding of what is done in healthcare, and what quality of care is being delivered

Why do these things drive administration?

A. Improved knowledge and capabilities increase administration

For a long period of human history, medical knowledge was limited and treatment was simple. Chest pain? Blood-letting. Rashes? Blood-letting. Cough? Try some prayer. If that doesn’t work we’ll do some blood-letting.

However, as medical knowledge increases, healthcare providers increasingly understand how to best treat a certain permutation of a condition (e.g. how do we best treat this patient with a heart attack with hypertension and chronic kidney failure who also is allergic to first line treatment). At some point, that knowledge becomes so extensive and intricate that it makes sense to specialize. This specialization is good for patients (who then can get treated by someone who knows that certain topic in great detail) and for practitioners (as they then can master a manageable amount of knowledge, rather than constantly looking up treatments and the latest research).

This results in a greater number of different types of providers that assess different parts of the patient. For example, in the US, internal medicine sub-specialization increased from 7% to 88% during 1951-2015. A greater number of specialized units increases the need of documentation and coordination; in other words administration.

100 years ago a patient would mainly meet their family practitioner and that practitioner would keep some medical records for their own sake. Today, a patient will meet their family practitioner, and have an average of 50 referrals sent during their life.5 These referrals need to be written, sent, documented, and their answers need to be read, attested and acted upon. The more healthcare specializes, the more coordination, documentation and administration healthcare needs.

(Note: Increased specialization isn’t just good, but has other costs beyond increased documentation. Higher sub-specialization means that specialists have less knowledge about other specialities. This means a potential bias to overestimate the advantages of treating conditions within one’s own speciality, and having a more limited understanding of other specialties/aspects of the patient’s health. This can result in a investigations/treatments that makes sense for a specialist but actually don’t help the patient, but have a net negative impact on their health. This viral discussion between two bear doctors makes the same point, and any clinician will see this and nod and say “Yep, it’s funny ‘cause it’s true”.)

B. Improved outcomes increase administration

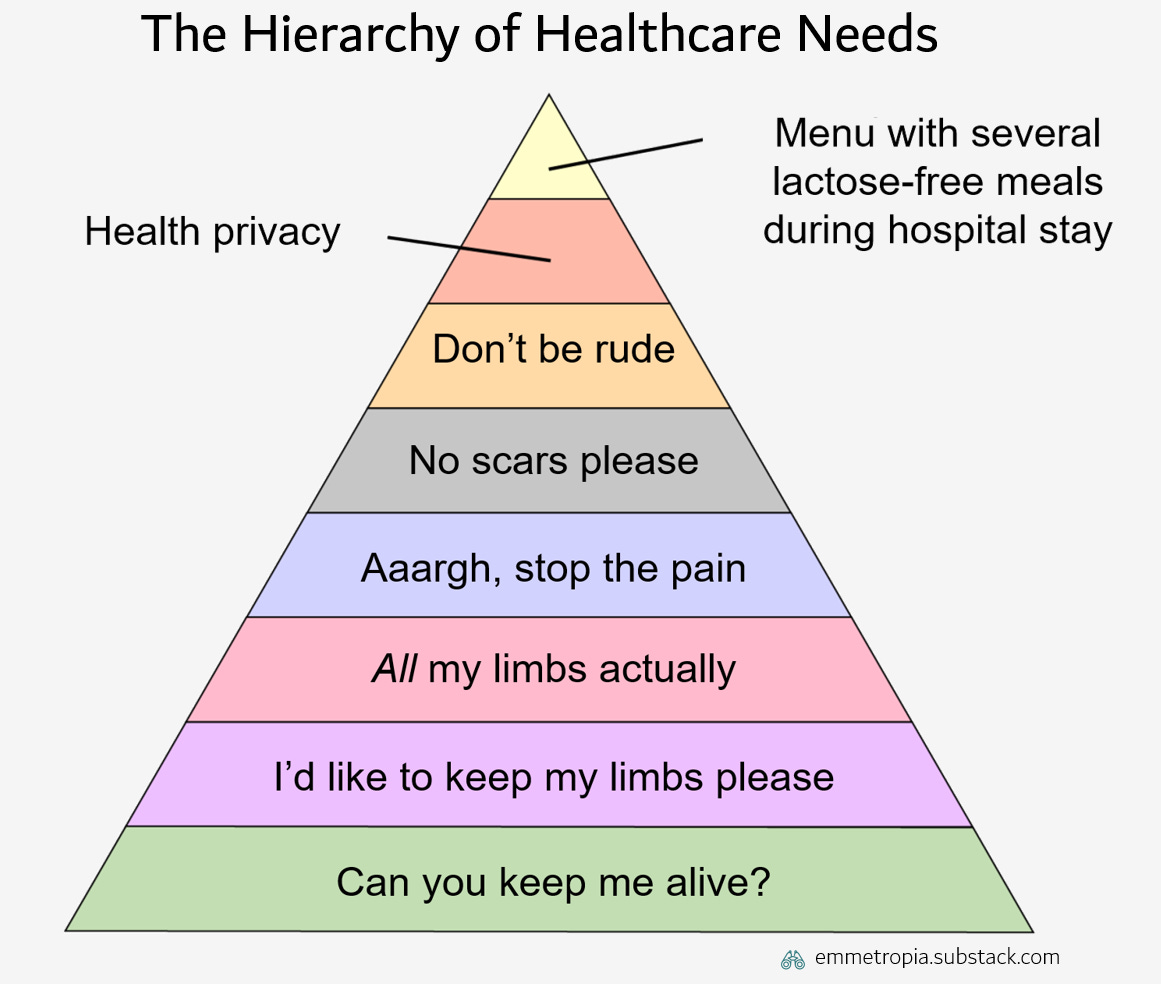

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a great model, but in this case I believe the less known Jonathan’s hierarchy of healthcare needs is more relevant.

Now, I’m not saying that being able to choose between several lactose-free meals following a medical procedure isn’t important.6 I’m just saying that there are other things which most people would deem much more important. There are also more steps not illustrated in the top of pyramid.7 As outcomes improve, two things happen:

Risk tolerance decreases. Providers will spend increasing amounts of time on preventing things, which entails coordinating and documenting things in greater detail (what medications were taken? has the patient pooped today? what exercise routine is most engaging and most effective for rehabilitation?). This in itself means more administration. Moreover, payors (those paying the providers) will work on measuring more things to ensure quality and minimize risks further. These measurements will also drive documentation and administration.

Patients’ preferences shift up the pyramid. As outcomes improve patients take fundamental needs for granted, but have additional preferences that they didn’t use to have. This causes healthcare systems to spend more time on non-clinical things like documentation or quality assurance. It’s only when patients start surviving surgeries and keeping limbs that we start feeling strongly about health privacy and equality of care.

C. Improved lifespan increases administration

Let’s distinguish between lifespan (how long someone lives) and healthspan (how long someone stays free from disease). If lifespan mainly increases (more than healthspan), each individual will have more contacts with healthcare than before. During the past 50 years ago the average life expectancy for a Swede has increased with 7 years. These additional years are a medical triumph, but also entail more healthcare consultations managing comorbid elderly, where coordination and documentation becomes even more important.

D. Improved transparency increases administration

It makes sense to increase transparency in healthcare. The better managers, decision-makers and patients can understand what care is being delivered, and in what way - the easier it is to find areas to be improved and to work systematically with improving the system.

Transparency entails making something visible, measurable or understandable for someone else. This will, inevitably, entail communicating or sharing some kind of data. This data needs to be created - and thus the administration monster is fed again.

For example, consider Sweden’s National Diabetes Registry: a national quality registry containing data on the care of ~85% of all diabetics between 50 and 79 years of age in Sweden. This data makes it easy for everyone to see what care is being delivered and is crucial for improving diabetes care. At the same time, collecting and inputting this data takes time.

Not only that, healthcare providers often have to report different types of data in different ways to several stakeholders. This can cause a lot of administrative work as there are no general standards for how to format or structure the data.

These principles suggest that the better healthcare systems become, the greater the need for documentation, coordination and administration will become.

III. The increasing administration isn't actually quite that bad

Wait, what?

First of all, administrators aren’t increasing as fast as some people think - the statistics are tricky. Second, even though the number of administrators is increasing, that might actually be good for clinicians. And most importantly: time spent on administration can be as important as time interacting with patients.

US administrators did probably not increase with 3200%

I couldn’t really understand where the 3200%-graph got its data and what assumptions it was based on.8 Kevin Drum does an interesting deep dive on the same graph, and summarized that the increase since 1970 is probably actually somewhere around 1000%. That's still a lot, but much less extreme in relation to increases in health care expenditure (600%) or number of health care workers (500%). By this estimate the relative increase of administrators to clinicians is around 2x (not 21x).9

Swedish administrators have increased, but so have clinicians

What about the Swedish data? Just like in the 3200%-case: the sexy truth-devil is in the statistical details.

If you dig up the original analysis you can find a couple interesting things. The FTE analysis covers the years 2010-2017, during which Sweden had a population growth of 8%. The analysis has two categories:

Nurses (grew by 2%): nurses, midwives, medical laboratory scientist

Administrators (grew by 36%) : administrators (“handläggare”) and managers (“ledningsarbetare”)

First, some of the administrators are clinicians. Looking into the definitions, the administrator group contains e.g. “pure” administrators like regional directors or head of IT (who don’t work clinically). However, it also contains roles like head of department, deputy head of operations and operation managers. The most recent article about Swedish healthcare states that more than 50% of managers are people from the nurse group. If 50% of the manager group are actually clinical staff, and you recount the numbers, then the nursing group would have grown by 4% and the non-clinical administrators by 30%. Still a huge difference, but a relative increase of ~8x, not ~18x.

Secondly, I believe it makes more sense to compare administrators to all types of clinicians, rather than just the separate groups of nurses or doctors. As a population grows it might make more sense for a system to increase a certain clinician category more or less. Grouping all clinicians captures the investment in clinical capacity (compared to administrative capacity), which looking at an individual profession doesn’t.

During 2010-2017 there was a total increase of 8200 administrators (36% increase) of which ~1300 were clinical managers, 1500 nurses (2%), and 4000 doctors (16%). Analyzing this in the two aggregated groups paints a different picture - an increase of 6900 (30%) administrators vs 6800 (8%) clinicians - a 4x relative increase, with clinicians increasing in line with the 8% population growth.

Please note, I’ve been unable to find better sources of data, so this is still quite speculative. Please send me any useful data you might have and I’ll update this section.

The take-home? Yes, the number of administrators has increased, but not as much as the clickbait-y headlines might suggest.

Growth in administrators can be good for clinicians

We’ve established that as healthcare develops, the need for coordination and documentation increases. We also know that clinicians dislike administration.10 So isn’t an easy solution to increase the number of administrators in line with the increased administrative burden on healthcare?

In other words, a greater increase in administrators compared to clinicians might actually be a good thing - offloading clinicians, and enabling them to spend more time with patients rather than on administrative tasks.

Some administration can be directly medically valuable

Administration is often discussed as a bad thing in healthcare settings. Sometimes the debate is more nuanced, and people agree that administration can be good, but that it simply takes too much time.

That’s a key concept: not coordinating or documenting can waste time and hurt patients. A study from 2010 exemplifies this. They looked at patients that got care at two institutions with two separate EMRs that didn’t communicate - and what care the patients got. Around 20% of the cases had at least one duplicate test that was entirely unnecessary. These tests help no one, take time, cost money, and can increase the risk of getting false positive results. But to prevent this, clinicians will only experience the increased admin, but not all the unnecessary tests or medical errors the admin prevents.

The 3 examples I mentioned earlier also illustrate this.

Lots of clicks just to enter the EHR: Yes, clinicians experience lots of logins. But those annoying logins are extra layers of security that increase the IT security from intruders, and create traceability to know if someone has been snooping around in someone’s chart for no reason (something that wasn’t possible with paper charts).11

Writing discharge notes for patients I’d never met: Yes, clinicians can be tasked with seemingly pointless paperwork. And writing a discharge note for a patient you’ve never met risks missing pertinent information. But the diagnosis codes in the discharge note is key for calculating the reimbursement to the hospital, as well as ensuring correct statistics on length-of-stay and many other quality metrics.

Transferring information to quality registries: Yes, those hours of work were mind-numbing - but they contributed to quality registries which have been central for research which in turn has improved healthcare.

In all three cases the administration does have benefits, but not for the clinician performing it. The benefits are for the patients (health privacy), payors (more efficient allocation of resources) and researchers (better data).

Can this trend of increasing administration be extrapolated indefinitely into the future? Will a clinician in year 2323 spend 85% of their time on administration ? Not necessarily. There is some hope.

IV. Time spent on administration can be managed

So if the need for administration increases as healthcare improves, and healthcare is improving - the total need for administration will continue for the foreseeable future.

Every second or third year you can read about a new initiative to reduce administration in healthcare. However, look carefully and you’ll see that these rarely end up in concrete changes. The initiative often starts with ambitious and shallow goals (“Admin is bad! Let’s get rid of 50% of all admin!”). But quite soon the task force realizes that virtually all admin has an underlying reason, that driving change in healthcare is complex, and the initiative fizzles out.

I think we can do better.

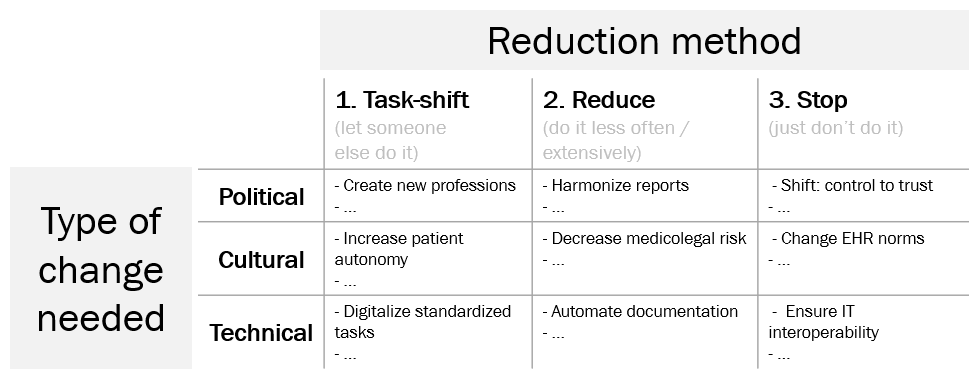

I’m not saying it’s easy to reduce administration, because it isn’t. But adopting a more nuanced view of what administration is can yield more effective initiatives. I find it useful to group administrative tasks by the reduction method, and what type of change is needed.

There are three ways to reduce admin: task-shift the administration (let someone else do it), reduce the administration (by doing it less often or less extensively) or simply stopping. However, often more fundamental political, cultural or technical changes are needed to reduce the administration. Let’s go through the table step by step.

1. Task-shift. To enable task-shifting of e.g. documentation, professional boundaries need to be redefined. One example is shifting documentation from physicians to medical scribes when EHRs were introduced in the US in the early 2000s. Existing professions may resist task-shifting, and this can quickly becomes a political question where unions and professional associations stop task-shifting. This may also require changes in laws (for example to let pharmacists treat extremely standardized and relatively low risk conditions like uncomplicated urinary tract infections).

However, there are also cultural barriers. Letting patients choose a time slot for when to meet a physician can have many benefits (reduced no-show rate, decreased staff labor, decreased waiting time, and improved patient satisfaction), but reduces clinician autonomy and shifts power to patients. Cultural barrier to these kind of changes should not be underestimated.

Finally, there are also technological barriers. There are many repetitive and fully standardized tasks which in theory could be fully automated. By digitalizing such tasks (such as digital history collection prior to meeting a clinician) the administrative task can be shifted to an automatic digital system rather than a person.

This last example isn’t purely technological, as digitalizing processes like history collection also entails large cultural changes. I’d recommend you to see the types of changes as dimensions that can overlap, rather than separate groups.

2. Reduce. The number of stakeholders (payors, governmental authorities, quality control organizations) demanding data from providers will only increase, as will the different types of data that they demand. Standardizing the reports that providers send to payors and other stakeholders would reduce the marginal cost of providing such data. However, achieving that will require negotiations between different stakeholders that want different types of data.

There are also cultural issues. Excessive documentation could be reduced by decreasing perceived litigation risk among healthcare professionals. If clinicians are afraid of getting complaints from patients, or getting sued by them, they might deviate from good practices (this is called defensive medicine). Defensive medicine seems to increase documentation. One consequence of the perceived risk is documenting more in the medical records - not as it will help the patient, but simply to protect oneself from a hypothetical future complaint/lawsuit. Addressing this requires a shift in culture.

Finally, documentation can be automated. Historically, healthcare has actually continuously become more efficient in documenting (writing on paper notes, dictation tools, medical secretaries or scribes, EHRs). However, the challenge is that the amount of data that providers are required to document has increased quicker than the increase in efficiency. Today, novel AI model-powered automated dictation tools offer a possible way to significantly reduce the amount of time spend on documentation.12

3. Stop. As discussed earlier, an increasing number of stakeholders demand increasing amounts of data from providers to ensure quality and efficiency. In theory, much reporting could be avoided if these stakeholders simply trusted that providers were performing as well as possible, instead of requiring data. However, I think its’s politically extremely difficult, if not impossible, to actively dismantle the ability to know how providers are performing and getting that accepted by voters or shareholders.

Much documentation is duplicated and redundant. Some of this can be explained by how EHR software is designed (where documentation has to be regurgitated and repackaged in a new note to be useful), but I believe the current documentation norms are even more important. Changing documentation culture and norms is difficult, but possible. I believe a significant part of documentation could be reduced if the culture shifted to value concise and short notes, and to devalue repeated information.

Finally, a lot of administration is due to different IT systems inability to communicate with each other, which forces providers to input the same data in different systems. As the number of IT systems in healthcare increases, it becomes increasingly expensive and complex to integrate the systems with each other. Therefore, ensuring interoperability (that the systems speak the same “language”) becomes increasingly important. If more providers demand that systems follow interoperability standards it will be much easier for the systems to communicate with each other.

Is any of the above easy? No, definitely not.

But if we really want to manage the increasing administration, we need to adress the political, cultural and technological aspects.

V. Emmetropes

Curious and inquisitive reader: thank you for sticking with me so far. Before we finish, let me summarize the eight key points which I believe we can conclude:

Administration in healthcare is…

Valuable: Administration takes time and resources which could be spent on clinical care, but can often have a high value for patients, providers or payors

Needed for coordination: Administration is critical for coordinating, controlling and improving healthcare

Caused by improvements: Administration increases as healthcare systems specialize or improve

Organic: Administration will increase over time and needs to be actively managed

Reducing administration requires…

Different methods: Administration can be stopped, reduced or task-shifted.

Multidimensional change: Reducing administration will often require political, cultural and technological change

Administrators (to some degree): Increasing the relative number of administrators (task-shifting) can be a way to offload clinicians

A deep understanding of why admin exists: Reducing administration is difficult, but continuously needed. Every couple of years people will anew complain about healthcare administration. Suggested initiative will often reflect a shallow understanding of the intricacies in healthcare, and that the underlying reasons administration is increasing is that healthcare is improving. Those initiatives will result in unactionable plans with limited impact, which fizzle out a year or two after the first press release.

P.S. This essay is based on an editorial I wrote in the Swedish Medical Journal a couple years back. If you belong to the small group of individuals that find this topic fascinating and important, have read this far and also speak Swedish, you can read the much shorter editorial here.

Issues with the graph: 1. Only using relative numbers (which can be misleading) 2. Unclear definition of how growth is calculated (the article clarifies that it’s compared to the first year) 3. Vague sources which make it difficult to understand underlying assumptions.

If you feel that my answer to this question is too shallow, please read Ezekiel Emanuel’s 452 page epic on this topic. It won’t make my simple definition look better, but hopefully it’ll buy me some time to write more on this topic before you have time to poke holes in my theory

A GP clinic in Sweden sends around 6 000 referrals per year for a population of around 10 000 patients, in other words 0.6 referrals per year. Assuming a life expectancy of 83 years, this gives an average of 49,8 referrals

I know several friends, or rather friends’ partners, who would ardently argue that lactose-free meals can have an oversized impact on their QALY

More realistic examples include for example: having quicker access to healthcare, being able to choose the sex of the healthcare provider, and being able to access medical records

1000%/500% = 2x, compared to 3200%/150% = 21x

This antipathy does unfortunately at times end up targeting administrators themselves. A great example is a letter to the editor from 1982 in the Canada Family Physician journal, where the articulate R. Marokus summarizes his nuanced, balanced and refined opinion with “I haven't met a single hospital administrator who wasn't a confirmed and profound horse's arse”.

However, there are some technical non-value creating logins which only waste time and need to be addressed. I will write more about that in the future

Here I also wish to propose The AI Law of Healthcare Administration: Any text discussing improving administration in healthcare, published after the 1st of January 2023, will mention AI in some form